Most crypto investors miss thousands in tax savings every year because they don’t understand how cryptocurrency taxes work. The IRS treats your digital assets differently depending on how you trade them, and one wrong move can cost you significantly.

At Top Wealth Guide, we’ve seen investors pay far more than necessary simply because they lacked a clear tax strategy. This guide walks you through proven tactics to reduce your tax bill while staying fully compliant.

In This Guide

How the IRS Actually Taxes Your Crypto

The IRS classifies cryptocurrency as property, not currency. This single distinction shapes everything about how you’ll pay taxes on your digital assets. According to IRS Notice 2014-21, every time you dispose of crypto-whether you sell it, trade it for another coin, or spend it to buy something-you trigger a taxable event. A Bitcoin purchase at $30,000 that you later sell for $45,000 creates a $15,000 capital gain. Exchanging Bitcoin for Ethereum counts as a sale of the Bitcoin, even if you never touched fiat currency. Most investors don’t realize this until they’ve already made dozens of trades and owed far more than expected.

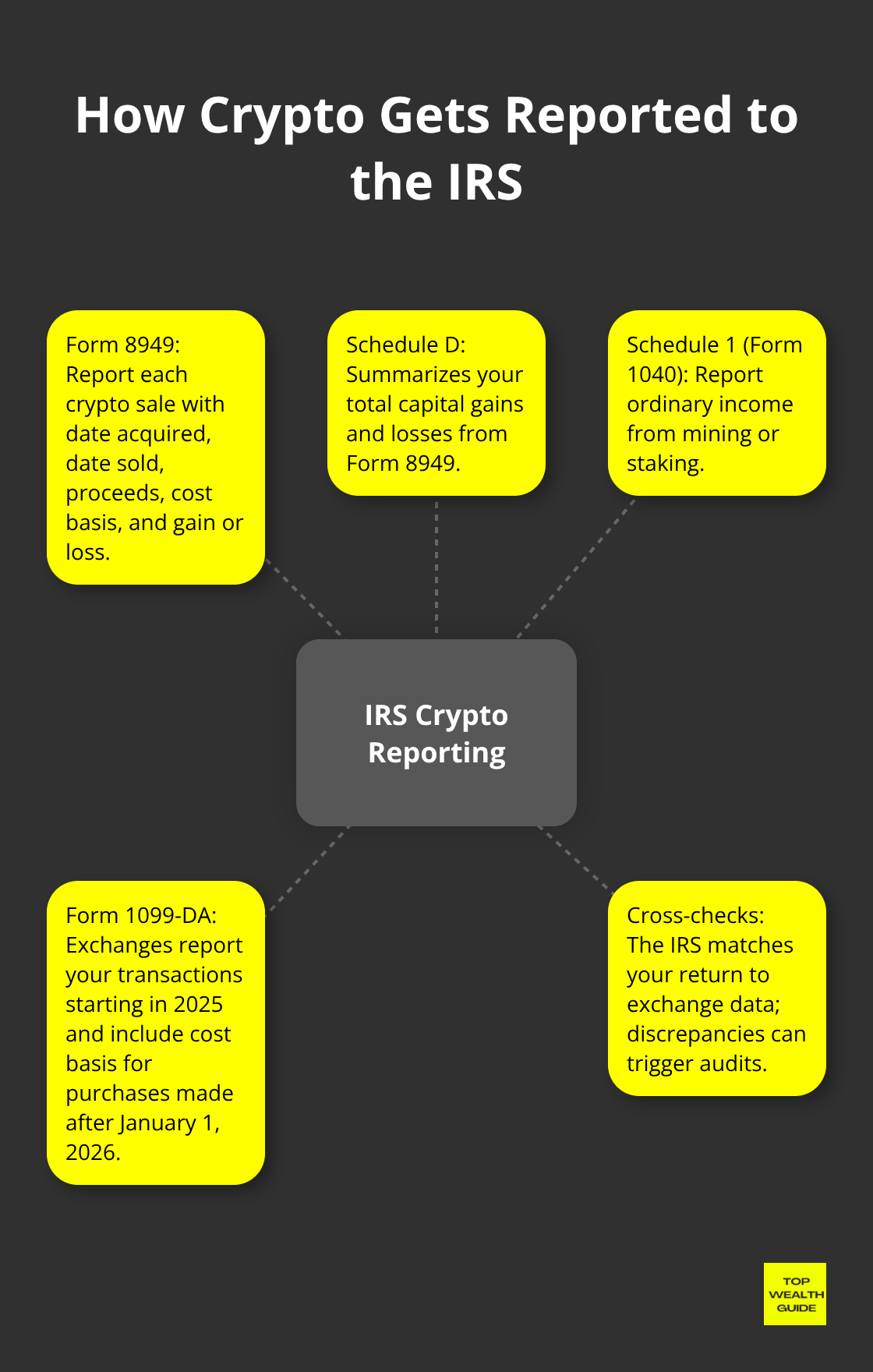

The IRS has grown increasingly aggressive in enforcement. Between 2019 and 2024, the agency issued over 1,500 crypto tax reports, and audits have risen significantly. Starting in 2025, exchanges are required to report your transactions directly to the IRS via Form 1099-DA, which will include cost basis for purchases made after January 1, 2026. This means the days of hoping the IRS doesn’t notice your crypto activity are over. Your exchange now reports directly to the government, so accuracy matters more than ever.

Income vs. Capital Gains: Where Most Investors Get It Wrong

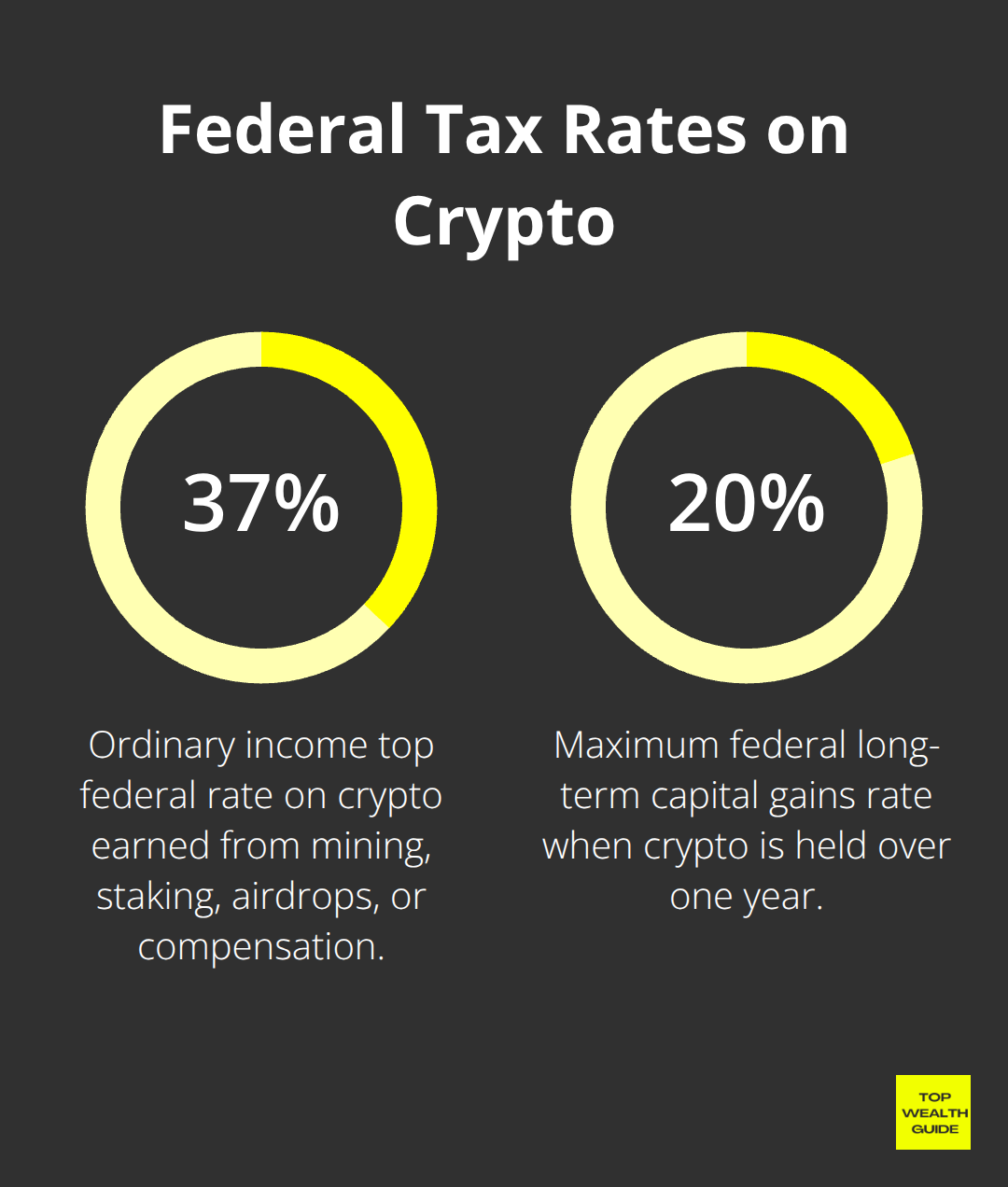

Your crypto faces two completely different tax treatments depending on how you acquire it. If you earn crypto through mining, staking, airdrops, or as salary compensation, that counts as ordinary income taxed at your marginal rate-up to 37% federally. You receive Bitcoin rewards from staking, and those rewards face taxation as ordinary income the moment you receive them, regardless of whether you touch them. Then, when you eventually sell that staked Bitcoin, you owe capital gains tax on the difference between your sale price and your original cost basis. This double taxation catches investors off guard.

The other path is capital gains, which applies when you dispose of crypto you already own. Hold it less than a year, and short-term capital gains rates apply-taxed as ordinary income, up to 37%. Hold it over a year, and you qualify for long-term capital gains rates capped at 20% federally. This timing advantage matters significantly.

A $50,000 gain taxed at short-term rates costs you $18,500 in federal tax. The same gain at long-term rates costs $10,000. That’s an $8,500 difference for waiting twelve months. Many investors rush to sell without considering this timing advantage.

Reporting Requirements That Will Catch You

The IRS now has multiple ways to track your crypto activity, and missing deadlines creates serious penalties. Form 8949 is where you report each individual crypto sale, listing the date acquired, date sold, proceeds, cost basis, and gain or loss. These roll up to Schedule D, which summarizes your total capital gains and losses. If you earned crypto income from mining or staking, Schedule 1 (Form 1040) is where that gets reported. The IRS can cross-reference what you report against what your exchange reports.

Discrepancies trigger audits.

Transfers between exchanges you own don’t create taxable events, but fees charged during transfers sometimes do-this creates confusion that auditors love to exploit. You must keep meticulous records showing the cost basis for every single transaction, especially for crypto transferred from other platforms. Many exchanges won’t automatically populate cost basis when you move coins, forcing you to manually enter it. Get this wrong, and the IRS assumes your entire proceeds are gains.

The Cost Basis Challenge Across Multiple Platforms

Cost basis errors represent one of the most common audit triggers for crypto investors. When you transfer Bitcoin from Coinbase to Kraken, your new exchange doesn’t automatically know what you paid for that Bitcoin originally. You must manually input this information, and most investors either skip this step or calculate it incorrectly. The IRS expects you to track cost basis across every platform you’ve ever used. If you’ve traded on five different exchanges over three years, you now face the burden of reconstructing that entire history. Professional tax defense cases show that investors who maintained detailed records across platforms avoided penalties, while those who didn’t faced substantial bills. The April 15 deadline for crypto tax reporting applies to all federal taxes. Missing this deadline costs 5% of unpaid taxes per month, up to 25%, plus interest. Proper documentation and accurate reporting can mean the difference between owing thousands and receiving refunds.

Understanding these reporting requirements sets the foundation for tax-loss strategies and cost basis methods that can actually reduce your liability. The next section shows you exactly how to calculate your cost basis and use losses to offset your gains.

Cost Basis Methods and Tax-Loss Harvesting

Understanding Cost Basis and Why It Matters

Your cost basis forms the foundation of every crypto tax calculation, and selecting the wrong method costs thousands. Cost basis represents what you originally paid for each unit of crypto, including acquisition fees. When you sell Bitcoin purchased at $30,000 and sell it for $45,000, your cost basis is $30,000 plus any fees you paid to buy it. The IRS lets you choose how to calculate cost basis across your holdings, and this choice directly impacts your tax bill. Most investors default to First-In-First-Out without understanding that other methods exist or that their choice matters significantly.

FIFO vs. Specific Identification: The Tax Impact

FIFO stands as the simplest method and the IRS default if you don’t specify otherwise. You sell your oldest coins first. Assume you bought Bitcoin in 2020 at $10,000 and again in 2023 at $40,000, then sold one unit in 2024 at $60,000. FIFO treats that sale as disposing of your 2020 purchase, creating a $50,000 gain. Specific Identification lets you choose exactly which units you sell, and this matters when your purchases happened at vastly different prices. Using the same example, you could specify that you’re selling the 2023 purchase instead, creating only a $20,000 gain. That difference saves you $6,000 in federal taxes at the 20% long-term rate.

The catch is that you must identify which specific coins you’re selling at the time of the transaction and maintain documentation proving it. Most exchanges don’t make this easy, forcing you to manually track lots across platforms. This complexity explains why many investors stick with FIFO despite its tax inefficiency.

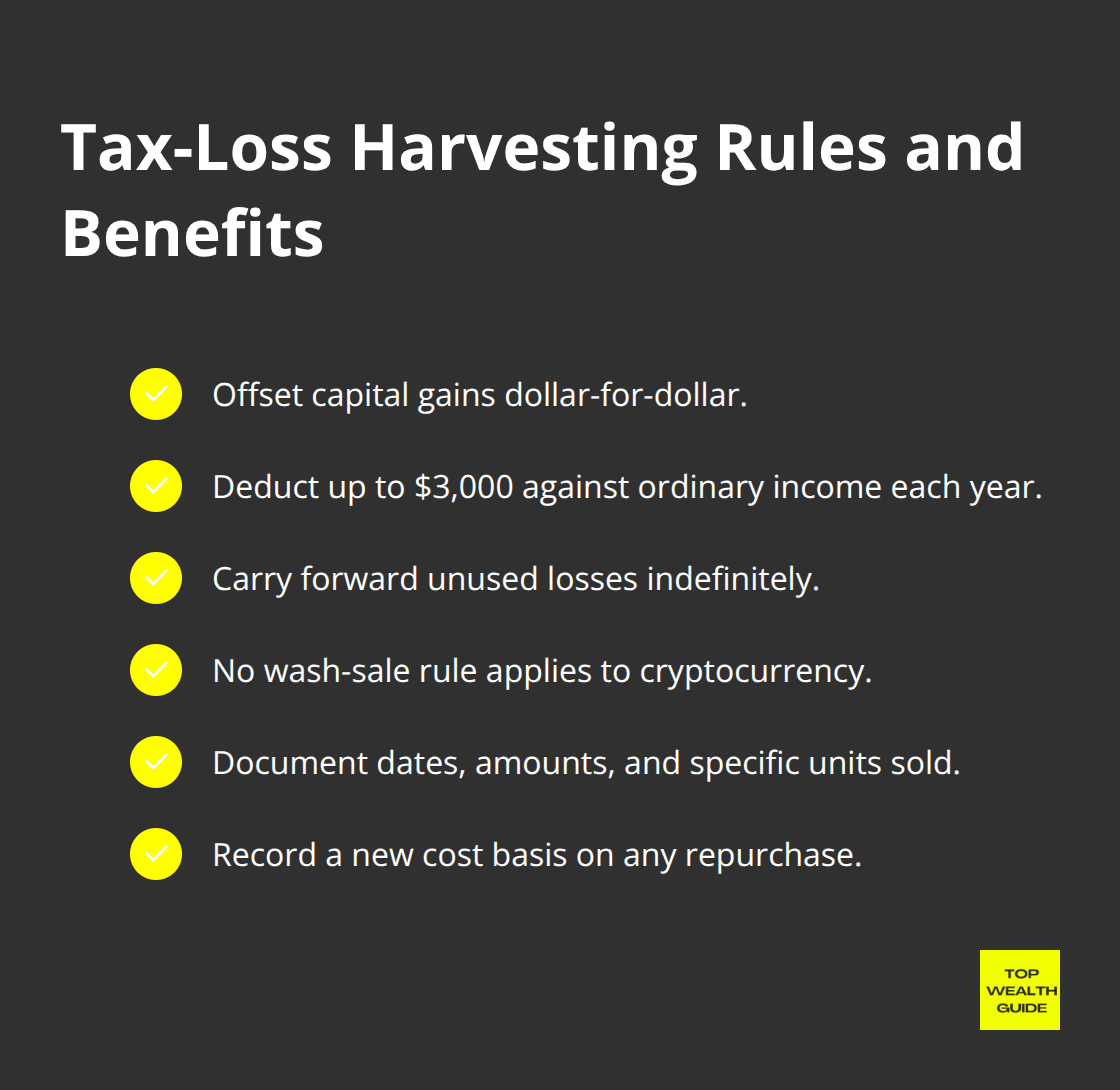

Tax-Loss Harvesting: Converting Losses Into Deductions

Tax-loss harvesting turns your losing positions into deductions that offset gains dollar-for-dollar. If you have $100,000 in capital gains from successful trades and $30,000 in losses from positions that declined, selling the losing positions eliminates $30,000 of your gains, reducing your taxable capital gains to $70,000. At the 20% long-term rate, this saves you $6,000 in federal taxes. The IRS allows you to deduct losses against gains with no limit, then deduct up to $3,000 of ordinary income annually.

Any losses beyond that carry forward to future years indefinitely.

A trader who realizes $100,000 in losses can use $50,000 against gains immediately and $3,000 against ordinary income in year one, then $3,000 annually against ordinary income in years two through seventeen, eventually using the full amount. The wash-sale rule does not apply to cryptocurrency. You can sell a crypto position at a loss and immediately repurchase the same asset without triggering wash-sale restrictions, making crypto tax-loss harvesting more flexible than stock strategies.

Executing Tax-Loss Harvesting With Discipline

Practical execution requires discipline and timing. Track your positions monthly and identify losses before year-end. If Bitcoin drops 30% in November, you still have six weeks to harvest that loss before the December 31 reporting deadline. Many investors procrastinate until December 15th, then panic-sell at market prices they didn’t expect. Planning earlier gives you control.

Document every loss harvest with the date, amount, and specific units sold. When you repurchase the same asset days later, maintain separate records showing the new cost basis. This separation prevents confusion during audits. An investor who sold Ethereum at a $20,000 loss in December then repurchased it in January must clearly show that the January purchase has a new cost basis, separate from the original position that was harvested. Failing to document this distinction creates audit risk when the IRS sees multiple transactions in the same asset.

Managing Cost Basis Across Multiple Exchanges

Cost basis calculations across multiple exchanges create the biggest practical challenge. An investor who traded on Coinbase for two years, then moved to Kraken, then used Uniswap for DeFi trades faces the burden of reconstructing cost basis across three completely separate systems. Coinbase might show your BTC purchase at $35,000, but when you transferred that BTC to Kraken, Kraken doesn’t automatically know your original cost basis. You must manually enter it. Many investors skip this step, and when they eventually sell on Kraken, the exchange calculates gains as if they bought the BTC on the transfer date for $0 cost basis. This inflates your reported gains substantially.

The 1099-DA reporting requirement starting in 2025 will include cost basis for new purchases, but it won’t retroactively fix positions acquired before that date. You own the responsibility for tracking this historical data. Crypto tax software like CoinLedger or Koinly can import transaction histories from multiple exchanges and calculate cost basis automatically. These tools cost $100-$300 annually but save far more in accurate tax reporting and audit defense. The software also handles Specific Identification tracking, letting you optimize which lots you sell without manual calculations. With your cost basis properly documented and your losses strategically harvested, you now control the timing of your sales-a power that separates tax-efficient investors from those who pay unnecessarily. The next section shows you how to weaponize this timing advantage throughout the year.

When Should You Actually Sell Your Crypto

The One-Year Threshold That Changes Everything

The timing of your sales determines whether you pay different tax rates on the same gain, yet most investors sell whenever they feel emotionally compelled rather than when the calendar serves them. A $50,000 profit on Bitcoin costs you $18,500 in federal taxes if you sell before holding for one year, but the identical profit costs only $10,000 if you wait past the one-year mark. That $8,500 difference isn’t theoretical-it’s real money that stays in your pocket instead of going to the IRS.

The one-year holding period creates a hard line in the sand. An investor who purchased Bitcoin on June 15, 2024 at $40,000 and watches it climb to $65,000 by May 2025 faces a choice: sell in May and owe short-term capital gains tax on the $25,000 profit, or wait until June 16 and qualify for long-term capital gains tax rates. Waiting twenty-six days saves roughly $4,200 in federal taxes. This math should influence when you actually hit the sell button.

Balancing Tax Advantages Against Market Risk

The challenge is that crypto prices don’t wait for your tax calendar. Bitcoin might peak in May and decline by June. Investors must balance the tax advantage of waiting against the real risk of market movement. The solution is planning your sales in November and December, when you have visibility into your year-end position and can execute before January 1 with full knowledge of your total gains and losses.

If you’ve already realized $100,000 in gains from earlier trades, you know you’ll owe substantial taxes regardless. This knowledge lets you use a tax loss harvesting strategy in December to offset those gains, then plan which positions to hold through the following year to benefit from long-term rates. Investors who wait until January to think about their prior year’s taxes have already lost control of the outcome.

Using Tax Software to Track Holding Periods

The practical execution requires tracking your cost basis and holding period for every single position. CoinLedger and Koinly both provide holding period tracking automatically, flagging which positions have crossed the one-year threshold and which ones haven’t. This clarity lets you make informed decisions about which coins to sell now and which to defer.

An investor with five Bitcoin positions (three held under one year and two held over one year) can choose to sell the long-term positions first if prices are favorable, deferring the short-term sales to a year when overall gains are lower. Detailed record-keeping across all your exchanges becomes non-negotiable here. When you’ve traded on Coinbase, Kraken, Uniswap, and a decentralized exchange, reconstructing which position has been held longest requires documentation that most investors never maintain. The IRS will not accept vague claims about holding periods. You need timestamps showing acquisition dates and sale dates for every transaction.

Organizing Exchange Records Before Year-End

Exchange statements provide holding period data automatically, but you must download and organize them before year-end. Waiting until April to gather this information nearly guarantees errors. The most tax-efficient investors conduct quarterly reviews of their positions in March, June, September, and December, identifying which trades have crossed holding period thresholds and planning accordingly. This quarterly discipline prevents December chaos and lets you execute sales when markets are calm rather than when tax deadlines loom.

Your tax software cannot make these strategic decisions for you-it can only calculate the tax impact once you’ve decided what to sell. The decision itself requires intentional planning based on your actual holdings and your specific tax situation.

Final Thoughts

Reducing your cryptocurrency taxes comes down to three core actions: understanding how the IRS classifies your transactions, calculating your cost basis accurately, and executing strategic sales throughout the year. Most investors treat cryptocurrency taxes as an afterthought rather than a planning opportunity, which costs them thousands annually. The difference between paying 37% on short-term gains and 20% on long-term gains justifies intentional timing-a $100,000 profit costs you $37,000 in federal taxes if you sell too early, but only $20,000 if you wait past the one-year mark.

The mistakes that cost investors the most are preventable. Failing to track cost basis across multiple exchanges inflates your reported gains and triggers audit risk. Selling positions without considering whether they’ve crossed the one-year holding period threshold wastes the long-term capital gains advantage. Ignoring tax-loss harvesting opportunities means you’re not offsetting gains that you could eliminate entirely. These errors compound over time, turning what should be a manageable tax bill into a substantial liability.

Your next step is to download your complete transaction history from every exchange you’ve ever used and organize it by holding period. Identify which positions have crossed the one-year threshold and which ones haven’t, then calculate your total gains and losses for the year. Consider using crypto tax software to automate cost basis calculations and holding period tracking-the $100–$300 annual cost pays for itself through accurate reporting and audit defense, and Top Wealth Guide provides practical strategies for managing your wealth across all asset classes, including cryptocurrency.