Benjamin Graham’s investment framework didn’t just influence investors — it rewired how millions think about markets. His playbook is ruthlessly simple: focus on what actually matters… buy assets worth more than you pay for them. That’s it. No hype, no hot takes — just margin of safety and common sense (which, admittedly, is in surprisingly short supply).

At Top Wealth Guide — where we look at market cycles without the romance — we’ve seen value investing principles deliver real results across different environments. This guide shows you exactly how to apply Graham’s timeless strategies to the stocks and opportunities available right now — step by step, practical, and unapologetically focused on returns.

In This Guide

What Makes a Stock Worth Buying According to Graham

Graham’s framework rests on a deceptively simple idea: most stocks trade at prices divorced from their real worth. That gap – between price and truth – is the fulcrum of whether you make money or lose it over time. Graham called that gap the margin of safety. It’s the only defensible reason to buy a stock. Without it… you’re gambling, not investing.

Margin of safety means you buy at a serious discount to intrinsic value so mistakes won’t kill you. Graham suggested buying at roughly 66% of intrinsic value or less. Not paranoia-just basic arithmetic. Pay $30 for a business worth $45 and you’ve already built a buffer. Market eventually wakes up to the value? You win. You were wrong about value? You still have a cushion. That’s the point.

How to Calculate What a Stock Is Actually Worth

Graham gave investors a blunt tool-the Graham Number formula-to estimate intrinsic value quickly. Formula: sqrt(22.5 × EPS × BVPS), where EPS is earnings per share and BVPS is book value per share. The 22.5 is not mystical – it’s the product of Graham’s caps: P/E of 15 and P/B of 1.5.

Example: EPS = $2, BVPS = $20. Graham Number = sqrt(22.5 × 2 × 20) = sqrt(900) = $30. That’s the ceiling a defensive investor should tolerate. If the stock trades at $22, the Price-to-Graham-Number ratio is 0.73 – potential undervaluation. The beauty: speed and discipline. You can screen dozens of names in minutes and flag candidates for deeper work. But caveat – the Graham Number favors stable, old-line businesses with positive earnings and tangible assets. It misprices fast-growth companies and asset-light businesses (software, brands) – it’s blunt, not clairvoyant.

The Real Work: Analyzing Financial Strength

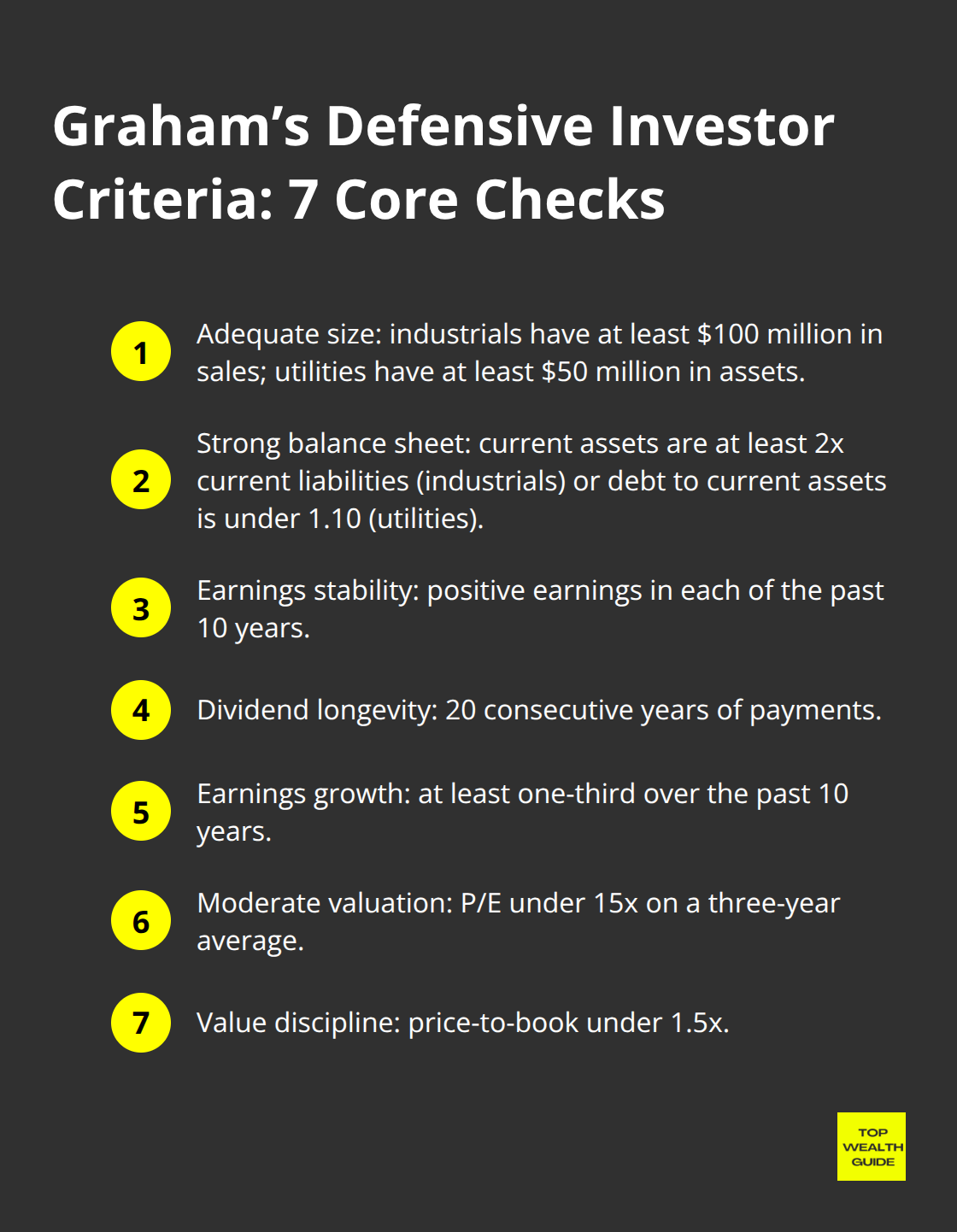

Price without financial context is noise. You must inspect the balance sheet and the earnings story to see if the valuation holds. Graham’s defensive investor criteria force you to check seven metrics – not because they’re sexy, but because they work.

First, adequate size: industrials – at least $100 million in annual sales; utilities – at least $50 million in assets. Scale matters; it buys you time. Second, a strong balance sheet: current assets at least twice current liabilities (industrials); total debt to current assets under 1.10 (utilities). Third, earnings stability – positive each of the past 10 years. Fourth, dividend longevity – 20 consecutive years of payments. Fifth, earnings growth – at least one-third over the past 10 years. Sixth, a moderate P/E – under 15x on a three-year average. Seventh, price-to-book under 1.5x.

These thresholds aren’t arbitrary-they’ve been stress-tested by decades of markets. Limit yourself to big, financially robust companies that pay dividends, grow earnings consistently, and trade at reasonable multiples-and you tilt the odds in your favor. Simple. Rare. Effective.

Why Financial Strength Matters More Than You Think

A weak balance sheet is a demolition crew in a downturn – and it will demolish your position regardless of how cheap the stock looks. Strong balance sheets are shock absorbers. Companies with low leverage and plenty of liquidity survive recessions, buy assets on sale, and keep paying dividends when others cut. That’s the difference between genuine value and a value trap – the latter looks cheap because it deserves to be cheap.

Graham’s seven metrics force you to pick companies that have already survived multiple cycles. They’ve paid dividends for 20 years – which means they didn’t die on the first recession. They’ve grown earnings – which means they can adapt. They have strong balance sheets – which means they can weather the next crisis. None of this is glamorous. It won’t trend on Twitter. But it separates profitable investing from speculation.

Now you know how to spot financially strong companies at reasonable prices. The next step is applying these principles in today’s market – where tech dominates and old-school metrics sometimes miss the mark. If you want to succeed, marry discipline with context – and refuse to confuse noise for insight.

Why Graham Works When Growth Fails

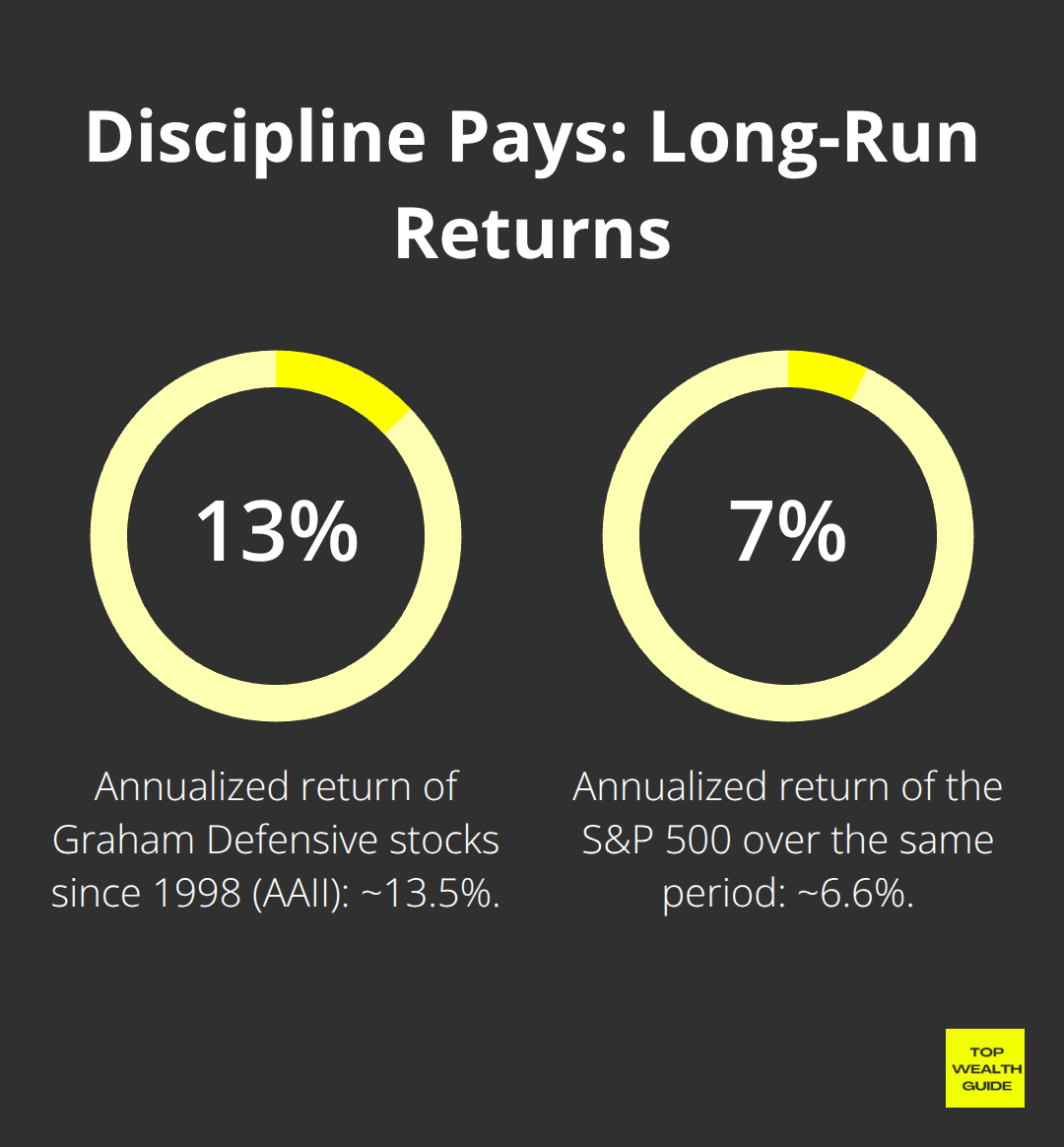

Graham’s playbook rests on an idea markets have largely abandoned: companies should earn money to justify their price. Novel concept – make cash, not just headlines. Growth and momentum investors pretend that doesn’t exist. They buy the fastest-rising names, worship disruption narratives, and treat price momentum as if it were a diploma. The math disagrees. AAII’s Graham Defensive Investor screen shows stocks that pass Graham’s seven tests returned about 13.5% annualized since 1998-versus 6.6% for the S&P 500.

That’s not luck. It’s discipline forcing a distinction between hype and reality.

Growth names regularly trade at multiples divorced from actual earnings-Tesla at roughly 70x earnings while a normal manufacturer sits around 12x. When the story shifts or growth sputters, multiples implode. Momentum traders panic-sell into the bloodbath. Graham’s margin of safety is literally insurance: buy at 66% (or some discount) of intrinsic value and the market has already priced in disappointment. Earnings stumble? You still own a business that makes money. That matters-especially in downturns. In 2022 growth stocks collapsed 50% or more; value stocks held up. Disciplined Graham investors had dry powder to buy into the wreckage. Momentum fans were cashing out precisely when they should have been buying.

Screening for Value in Tech-Heavy Markets

Problem: today’s economy is dominated by intangibles. Software firms have little tangible book, so the old Graham Number becomes a blunt instrument. Tech trades on future growth, not current earnings. That doesn’t kill Graham-it demands adaptation. Start with four metrics that still matter everywhere: earnings stability (profits every year), earnings growth (at least a one-third lift over ten years), moderate valuation (P/E under 15), and financial strength (debt-to-assets under 1.10).

Add a filter for return on equity north of 12%-a proxy for capable management and efficient capital use.

Microsoft passes these tests-yes, it’s trading at roughly 32x trailing earnings, but it posts 42% ROE and steady earnings growth. High P/E? Justified by real earnings power and a fortress balance sheet. Contrast that with unprofitable software plays at triple-digit multiples-these fail every Graham test. Practical rule: don’t banish tech – require it to clear the four universal gates plus strong ROE. If it hasn’t shown sustained profitability, it fails instantly. Most venture-backed startups won’t survive the screen-and that’s precisely the point. You separate genuine durable value from speculation wearing growth lipstick.

Real Opportunities in Today’s Market

Value isn’t hidden-it’s boring. Regional banks with solid loan books, established financials, manufacturers smoothing out supply chains, dividend-paying energy producers-they trade below intrinsic value because they lack a sexy narrative. A regional bank at 0.8x book with a 4% dividend and steady earnings? Meets Graham cleanly. The market yawns-your edge.

Energy companies face genuine structural questions from the transition, yet several major producers sit at single-digit P/Es with 4%+ yields and lots of free cash flow. The market has priced in permanent decline; reality suggests decades of profitability. Pharma firms with mature portfolios often trade at 10–12x earnings and return 3–4% in dividends-predictable cash flows, strong balance sheets. None of this trends on social, which is why it trades at discounts. Boredom, in this market, equals opportunity.

How to Execute the Screening Process

Make it mechanical. Use a screener: P/E < 12, debt-to-equity < 1.5, positive earnings for the past decade, dividend yield > 2%. You’ll get dozens of names. Then do two hours of actual work on the top five-read the 10-Ks. Ask: are earnings stable? Is management competent? Is the industry in secular decline? Most investors skip this part and chase what’s hot. That laziness creates your margin of safety.

Once you have names that pass Graham’s tests, the next move is portfolio construction and timing-knowing when to act versus when to sit tight. Markets hand you opportunities when everyone else is selling their soul for momentum. Be ready.

Where Graham Investors Go Wrong

The Trap of Overpaying for Quality

The biggest mistake Graham investors make – and it’s a doozy – is paying too much for quality. You spot a company with 20 years of uninterrupted dividends, a fortress balance sheet, and steady 8% annual earnings growth. It looks perfect on the checklist. Then you notice it trades at 18x earnings instead of your 15x target. You rationalize: the quality justifies a premium. That rationalization kills your returns.

Reality check: AAII data shows Graham Defensive stocks returned 13.5% annualized since 1998 not because they were the flashiest businesses, but because they were good businesses bought at genuinely cheap prices. The margin of safety evaporates the moment you pay full price for quality. A company worth $50 per share at 15x earnings becomes a mediocre investment at $55 – you’ve compressed upside and eliminated your buffer. Discipline means walking away from good companies at fair prices and waiting for them to become great values. Most investors can’t do this. They chase quality and then wonder why their returns lag.

Reading Market Sentiment Without Abandoning Discipline

The second mistake is treating Graham’s framework like a mechanical vending machine – run the screen, buy the names, hold forever. Markets reward timing within discipline. When the S&P 500 trades at 20x earnings and value stocks sit at 10x, load up. When valuations invert and Graham candidates reach 16x, trim or wait. Michael Burry’s fund didn’t win because he blindly held everything – sentiment matters.

You’re not ignoring the market; you’re reading it differently. If everyone sells boring dividend stocks to chase AI, that creates your opportunity window. Ignore sentiment and you’ll buy at 12x when the stock deserved 10x – because you followed a formula instead of asking whether the price actually moved.

Spreading Risk Across Sectors

The third mistake wipes out more Graham portfolios than any spreadsheet error: sector concentration. You screen for Graham stocks and end up with eight regional banks, three utilities, and two pharma names. All pass the tests. All look cheap. Then regional banking faces deposit flight, utilities get hammered by rising rates, pharma hits pricing headwinds – and your portfolio falls over in unison. Looks diversified on paper; behaves like a single bet in practice.

Graham’s seven criteria protect against company failure, not sector rot. True diversification means owning value across industrials, financials, energy, healthcare, and consumer staples. If you can’t find top stocks across at least four sectors, your opportunity set is too narrow – either valuations are uniformly high (time to wait) or your screen is too strict.

Position Sizing Over Stock Picking

Then there’s the classic compounding error – overweighting your highest-conviction picks. You find a regional bank at 0.75x book with a 5% yield and load up to 15% of the portfolio. One bad quarter, one regulatory tweak, and that conviction becomes a liability. Position sizing matters more than picking the “perfect” stock.

A portfolio of 12–15 Graham names, each sized at 6–8% of capital, with exposure to at least three sectors, survives the volatility that destroys concentrated bets. The mechanics work – but only if you respect the boundaries: buy at genuine discounts, adjust for market cycles, and spread risk across industries instead of hunting the deepest value in one corner of the market.

Final Thoughts

Benjamin Graham’s framework endures because it forces you to answer the question most investors dodge: what is this business really worth? That single discipline separates wealth builders from story-chasers – the former think like owners, the latter trade rumors and paper hopes. Graham’s margin of safety, intrinsic-value math, and balance-sheet hygiene aren’t quaint relics…they’re the scaffolding that keeps compounding honest.

You buy slices of real businesses that earn money, return cash to shareholders, and fortify their sheets. When panic hits and prices crater, you have dry powder to buy at genuine discounts. When mania blows multiples into the stratosphere, you sit – instead of sprinting after momentum. Over decades that behavior compounds – slowly, maddeningly reliably. The practical path is simple (and boring – which is the point): screen for Graham’s core checks – companies with > $100 million in sales, debt-to-assets under 1.10, positive earnings for ten consecutive years, and P/E ratios under 15 – then read the 10-Ks to understand the economics and judge whether management can actually run the business.

We at Top Wealth Guide focus on practical strategies that work in real markets, and our investing guides cover stocks, portfolios, and long-term wealth building with the same discipline Graham demanded. These principles aren’t theoretical – disciplined investors have seen 13.5% annualized returns since 1998 versus 6.6% for the broader market. Start screening today.